NB: THIS POST IS CURRENTLY STILL A WORK IN PROGRESS!

Frank Vizetelly's Illustrative Reportage of the America Civil War for the Illustrated London News.

The cover of the April 1961 edition of National Geographic, in which their first commemorative centennial Civil War features appeared, is graced by one of Vizetelly's many evocative images, as originally featured in the Illustrated London News.

In an earlier post I talked about my quest to rediscover a sequence of battlefield maps, produced by National Geographic (henceforth NG, for the sake of brevity) as part of their commemorative series on the centenary of The American Civil War. I was a little disappointed at the mismatch between my memories of these maps and the reality - a theme I will be returning to in a future post - but I was more than consoled by rediscovering the fabulous engravings made after sketches by British illustrator, journalist, and adventurer, Frank Vizetelly.

Frank Vizetelly, photographed by famous Civil War photographer Mathew Brady.

Initially I thought of and referred to these fantastic engravings as 'the wonderful work of Mr Vizetelly', or words to that effect. Then I read the article 'Witness To A War', by Robert T. Cochran, in the above pictured April 1961 issue of NG. In Cochran's feature I learned that, in fact, Vizetelly sent over sketches and written accounts. Once these reached England a team of anonymous engravers was set to work, turning his reportage into the gorgeous graphics that graced that rather splendid organ of metropolitan edification, The Illustrated London News (henceforth ILN).

Vizetelly was steeped in the booming tradition of illustrated news. Here's an extract of what brittannia.com says about the Vizetellys:

'Vizetelly family, originally spelled Vizzetelli, family of Italian descent active in journalism and publishing from the late 18th century in England and later in France (briefly) and the United States.'

Frank's father, James Vizetelly, had published Cruikshank’s Comic Almanack, featuring the comic engravings of George Cruikshank [1], whilst his brothers Henry and James founded the Pictorial Times and Illustrated Times, short lived ventures aimed at competing with the ILN. Indeed, never one to be left out of the action, and prior to the American experiences depicted here, Frank Vizetelly had himself helped found a similar pictorial periodical, launching Le Monde Illustré in Paris.

(16) "The fight for the rifle pits in front of battery Wagner." Frank Vizetelly Drawings, 1861-1865 (MS Am 1585). Houghton Library, Harvard University.

Above is Vizetelly's original sketch for The fight for the rifle pits in front of battery Wagner, the engraved version of which appears on the front of the NG April '61 issue.

The above image shows the original whole page context of this particular illustration, which also featured a depiction of action at Fort Sumter.

The NG cover is cropped and slightly colorised. So here, above, is the original engraved artwork in full.

'He excelled at his exacting trade because he threw himself without reserve into the stories he covered', enthuses Robert T. Cochran, even going so far as to compare Vizetelly to Virgil! Vizetelly certainly seems to have embodied one of Tom Waits' many memorable phrases, being something of a 'raconteur and roustabout'. A garrulous adventurer with a taste for living dangerously, he was able to charm his way into all sorts of situations, getting up fairly close (if not perhaps personal), to President Abraham Lincoln, in the White House, and later documenting 'government by the side of the road', as a witness to the end of Jefferson Davis' run as president of the Confederacy. And Vizetelly didn't just make a bee-line for the bigwigs, he would follow the armies, mixing with the rank and file, witnessing everything from domestic life to scenes of conflict and death, both on and off the battlefield.

This scene from Bull Run (also known as Manassas), in which overconfident Union troops ended up ignominiously taking flight, their rout becoming known as 'the great skedaddle', would land Vizetelly in trouble with his Union hosts.

Frank had arrived in Boston on the Liverpool packet, from there journeying south to join the Federal Army. Coming direct from England in what one supposes would be viewed as a semi-official position, decorum dictated he start out with the legitimate government. This he duly did, documenting troubling scenes in the powder keg period when New York itself temporarily turned into a macrocosm of what lay in the store for the country as a whole. With open war on the streets, vigilante lynchings, and attacks on an orphanage for black children, clearly not all Northerners were singing from the same hymn sheet! A little later on I'll explore where Vizetelly may have stood on some of these issues. But one thing's for certain, he didn't shy away from documenting every aspect of this highly contentious facet of the war.

Initially Vizetelly was covering the war from the Union end, here gaining access to the Prez himself, along with metropolitan dandies and buck-skin clad frontiersmen.

Vizetelly records 'Honest Abe' reviewing the troops in the early days of the conflict. Lincoln is stood by the flagpole; seated centre is the corpulent and elderly Lt. Gen. Winfield Scott, at the time C-in-C of the Federal forces.

But despite meeting uncle Abe, seeing such exotic Union troops as the Fireman Zouaves heading off to war, and accompanying Union troops in various scenarios, Vizetelly wanted to get where the real action was. Like compatriot William Howard Russell, the Times' correspondent in America, Vizetelly was destined to suffer from the fall-out around coverage of the Battle of Bull Run.

Russell had sent off a piece to the Times, disparaging Union efforts at this battle, earning himself the scornful nickname 'Bull Run Russell', and the disapprobation of Union authorities, who revoked his permit to accompany the Federal troops. Vizetelly also sent back coverage, including the 'skedaddle' scenario pictured above, and this lead to his credentials being cancelled as well. Hit I. Addition to this, after 'Old Fuss 'n' Feathers', Lt. Gen. Winfield Scott, got the heave-ho, and Gen. George B. McClellan's star came into the ascendant, the irascible chancer Vizetelly saw clearly how the wind was blowing.

As McClellan's large, well-trained and equipped army sat on its ass, Vizetelly, confined to the Washington DC locality, complained 'I am almost at a standstill for subjects for illustration', observing wryly that the only notable activity at the time was that of 'the greedy hordes of hungry contractors, who are determined to have their pound of flesh from the sorely pressed Union.' [2] Such forthright candour - which to a contemporary reader appears not inky unbiased, but even sympathetic to the North - did little to enamour him to powers within the Union at the time.

'Our special artist' (what a nice job title!) at the camp kitchen of the 2nd New York Regt. Concerning this picture, the ILN said 'we are happy to see, that he is able, amid the fears and anxieties consequent on a campaigning life, to attend in some degree to his creature comforts.' [3]

So by the time McClellan headed down the Virginia Peninsula, Vizetelly's 'credentials were cancelled, and he was left behind' [4]. So he headed West, for the Mississippi. Experiencing the enormity of the land through which he travelled, he exclaims: 'Oh! How many times since starting have I bemoaned the extent of this 'Almighty big country.'' [5]

After witnessing the crushing defeat of the Confederate Navy at Memphis, Vizetelly decided to slip across the lines and see if life with Johnny Reb might be more conducive to his taste for thrills and spills, and provide him with more exciting fodder for his newsfeed. According to his own reports of this cloak and dagger episode - he was hidden in a dug-out canoe amidst reedbeds for two days - Vizetelly managed to remain true to his bon vivant nature (he loved his food and drink!) dining on fresh oysters during this tense and potentially very dangerous escapade! He made his way to Richmond, and from this point onwards he stayed with the Southern team.

Destruction of the Confederate flotilla, off Memphis.

Once he'd made this switch, he couldn't very easily go back - some of the Union Generals were notorious for their views that all journalistic types were effectively spies, and ought to be treated as such, i.e. summarily shot! - besides which, I'm not at all sure he wanted to. Which brings us back to where he stood on the whole shebang. Considering a small selection of his images, some of which I reproduce below, we night plausibly infer or deduce some of the following: first, as suggested by the image below, Vizetelly implies that the slaves' lives in the South aren't so bad:

[image: (1) "'Barbarous' treatment of the Negro in the Confederate Camp, nights by the pine wood fire."]

Interestingly, Vizetelly was also able to depict such things as are shown in the next two images without, it would appear, connecting them in any way, ironic or otherwise, with the sentiment expressed in his 'Barborous treatment' artwork. For many modern viewers, less accustomed to seeing such things in daily life, these make for some rather unsettling viewing. In them African Americans become mere objects: objects to be sold, or objects to be withheld like property, as 'contraband of war', and lastly, as objects subjected to the expression of vengeful hatred.

A Southern slave auction.

A mob lynching. This scene is, oddly perhaps, and especially to those unfamiliar with the detail of the war, from the period of rioting in New York, just as the nation was sliding into full blown war. All kinds of mixed views, amongst which were both racism and anti-war feelings, manifested in the North as well as the South.

As great a contribution as Vizetelly makes to the artistic heritage of this conflict, one does have to wonder about where he stood on some of the fundamental issues. Meg Thompson puts it well when she says, 'As often happens, the artist fell in love with his subject.' Perhaps in part this was because of some streak of that romantic penchant for the cause of the underdog, which, under the banner of seccession for States' Rights, could almost impart to the South's cause something of a noble libertarian patina. But if that liberty was to be bound up with the right to enslave others... well, that rather takes the shine off! I also rather suspect, with 'Contraband of War' as exhibit A, he may have partaken of less than forward looking views in terms of race relations.

'Contraband of War' is the title of this illustration!

Indeed, such was his sympathy with the South, that a book has been written entitled The Confederacy's Secret Weapon: The Civil War Illustrations of Frank Vizetelly, by Douglas W. Bostick. Vizetelly himself summed up his feelings with these words:

'The more I see of the Southern Army the more I am lost in admiration of its splendid patriotism, at its wonderful endurance, at its utter disregard for hardships which, probably, no modern army has been called upon to bear up against. Surrounded as I am by the Southern people, living in their midst, associating with their soldiers, I emphatically assert that the South can never be subjugated.'

It's interesting that someone like Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain, a Union General famous for his role in Gettysburg, shared Vizetelly's admiration for the spirit of the South, and for the prowess of its fighting forces.

But, apart from some undertones in a picture like 'Contraband', one doesn't get such a clear picture of how Vizetelly felt about the oxymoronic and frankly hypocritical position that lay at the heart of the Confederate stance: they wanted to preserve their liberty, via States' Rights, in order to deprive others of theirs, via holding onto slavery. Even staunchly Secessionist Confederate diarist Mary Chesnut could see, and lament, the hypocrisies inherent in the lifestyle of the South, although her observations hinged mainly on the way Southern 'gentlemen' treated womenfolk.

Mary Chesnut's diary, as featured heavily in Ken Burns' The Civil War. Yet more potential reading matter!

So, whilst his stance on racial issues and slavery is, perhaps, a little unclear, it is crystal clear that he became a Southern sympathiser. His stance on the respective sides can be further deduced by considering a pair of sketches, and the resultant prints, entitled 'Union Troops attacking Confederate Prisoners in the Streets of Washington', and 'Camp of Federal prisoners on 'Belle Isle' Richmond, Virginia'. The former shows Confederates being berated in the Northern capital, whilst the latter show Union troops at ease in a well appointed camp. The obvious implication here is that the North mistreats its prisoners, but the South doesn't. We can only assume or hope he was at this point unaware of Camp Sumter (also known as Andersonville Prison).

But putting such weighty issues to one side for a moment, as lovers of military history, we can certainly applaud Vizetelly for covering such a large and diverse range of the action. As the images reproduced here attest, we get the politicians, the generals, the soldiers, and the people. We also get the landscapes, from the prairies and plains to the woods, from the cities to the forts, and those temporary towns and cities of armies on the move. We get marine warfare, sieges, ambushes, snipers, picket duty, parades, infantry battles, cavalry engagements, artillery fire, meleés, supply trains, corporal and capital punishments, and all sorts of other scenes.

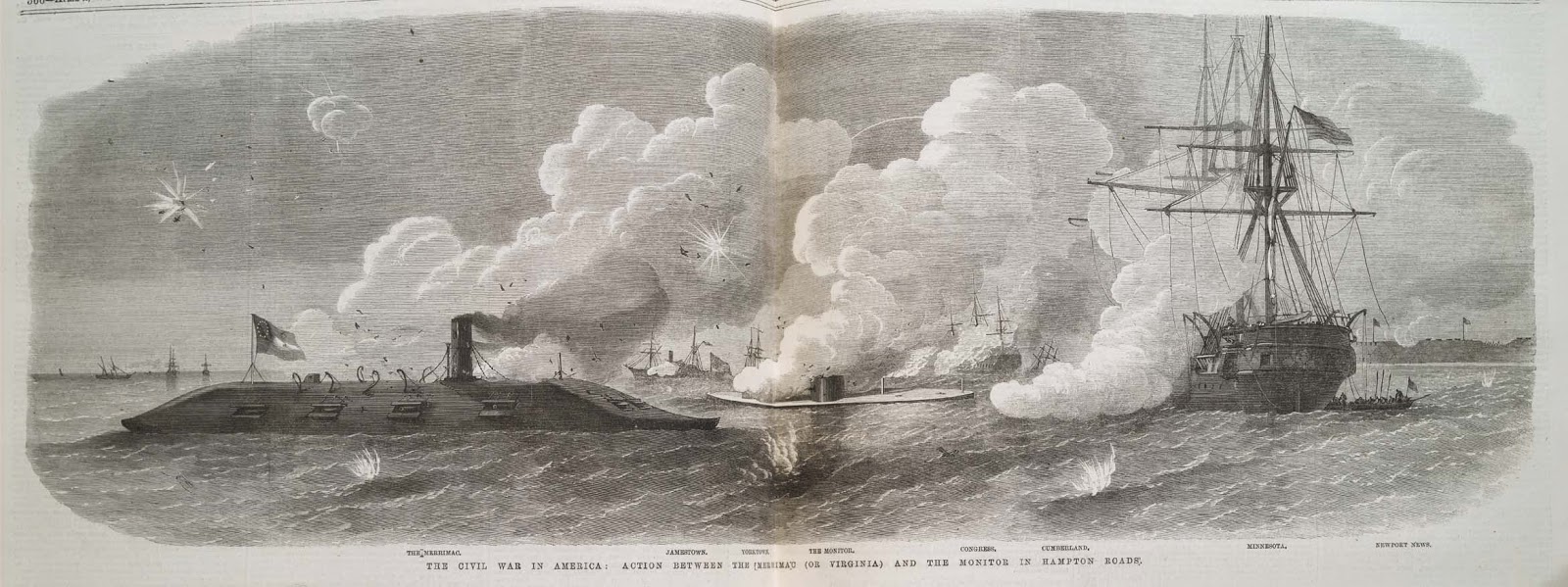

The following series gives the viewer a tase of the richness of Vizetelly's output, covering several 'genres', each illustrated by pair of images. Here we have two naval scenes, two 'sublime' landscapes, two figure settings, and finally two battle scenes. These images, rich and diverse as they are, and even when taking into account all the others by Vizetelly also shown here, still only represent a small fraction of the incredible output that resulted from his collaboration with The Illustrated London News.

The famous iron-clad duel, between the Merrimac and the Monitor, in the Hampton Roads.

A fantastic evocation of turbulent seas, both a literal illustration of a specific event (the passage of the Hatteras Bar), and a metaphor for a nation at war with itself.

And we ought also to pause to remember and celebrate those 'unknown soldiers', not just of the battles depicted, but in the engraving department, whose unsung toils bequest us these simply stunning images, some of which give Ken Burns' beautiful landscape shots a run for their money, and they do it without the benefit of stirring folksy music. Contemplate, if you will, the sublime and awful power of landscape and the elements in these two works.

It's worth noting that the Hatteras Bar illustration, above, depicts a scene in which Vizetelly, on board one of the boats shown pitching in heavy seas, was nearly lost overboard, and that during the thunderstorm he pictures below, which was the most violent he'd ever seen, he was aboard a ship carrying a large tonnage of munitions! As powerful as the images themselves are, if you imaginatively project yourself into his situations... well, he certainly didn't lack for courage!

It's worth noting that the Hatteras Bar illustration, above, depicts a scene in which Vizetelly, on board one of the boats shown pitching in heavy seas, was nearly lost overboard, and that during the thunderstorm he pictures below, which was the most violent he'd ever seen, he was aboard a ship carrying a large tonnage of munitions! As powerful as the images themselves are, if you imaginatively project yourself into his situations... well, he certainly didn't lack for courage!

A stormy night on the Mississippi: what a great picture!

Another instance of the sublime forces of nature as a setting for the tragicomedy of human life. Here, across the Great Falls of the Potomac, pickets can either pick each other off, or just enjoy the view. 'Soft falls the dew on the face of the dead, the Pickett's off duty forever.' [footnote: source]

[insert another pair of paired images, one showing smaller groups of figures, and another showing battlefield scenes]

Turning from the rich diversity of the art that resulted from Vizetelly's peregrinations, let's pause to look at his process. Almost all of the ILN engravings in my post are derived from an archive held in the libraries collections of the Beck Centre of Emory University, gathered in a project under the auspices of Sandra J. Still and Emily E. Katt.

But these images are the work of the unknown engravers. To see what they worked from we need to look at images held in the Harvard Library, such as the sketches in the following series. In each instance I've paired an image sent back by Vizetelly with the resulting ILN engraving, and in one or two instances I've also shown the verso (or the back, in plain English) whereon Vizetelly has scrawled written info to supplement that which he's conveyed graphically.

(5) "Scene on the Tennessee River - Confederate Sharpshooters stampeding Federal waggons." Frank Vizetelly Drawings, 1861-1865 (MS Am 1585). Houghton Library, Harvard University.

Above, the sketch for Scene on the Tennessee River - Confederate Sharpshooters stampeding Federal wagons. Below, the final engraved artwork as it appeared in the ILN.

(22) "Assault on Battery Wagner, Morris Island, near Charleston, on the night of the 18th July - The rush of the garrison to the parapet." Frank Vizetelly Drawings, 1861-1865 (MS Am 1585). Houghton Library, Harvard University.

Above, the sketch for Assault on Battery Wagner, Morris Island, near Charleston, on the night of the 18th July - The rush of the garrison to the parapet. Below, the final engraved artwork as it appeared in the ILN.

(25) "Battle of Chickamauga - the Confederate General Hood receiving his wound." Frank Vizetelly Drawings, 1861-1865 (MS Am 1585). Houghton Library, Harvard University.

Above, the sketch for Battle of Chickamauga - the Confederate General Hood receiving his wound.

Below, the final engraved artwork as it appeared in the ILN.

Of course, before his images and text could be rendered as engravings and articles, the material had to get back to England. During his spell under the rubric of the Union he could do this via official channels, but once he'd switched sides, he had to smuggle his reports back. The situation demanded that, with a semi-piratical finesse he no doubt savoured, his missives 'run the blockade', something which he also did in person on occasion, as the picture below attests.

Indeed, such was the potency of his work that it became a sought after form of contraband itself. Meg Thompson writes, as part of a series called 'Drawing The War', that 'The Union was aware of Vizetelly’s whereabouts, and a bounty was offered to the Union Navy if they captured his sketches aboard any detained ships.' As a consequence of this situation, there were occasions on which Vizetelly's work, haivng been intercepted, would appear, uncredited, in Northern publications, such as Harper's Weekly.

All in all, I think Vizetelly's exploits in America during the Civil War make for a fascinating story, and his artwork and writings are an invaluable resource, both in their rawer annotated sketch states, and also in their more fully realised ILN format, as engravings, often accompanied by his lively reports from the scene of the actions depicted.

Vizetelly aboard the Lilian, running the blockade into Wilmington harbour.

Indeed, such was the potency of his work that it became a sought after form of contraband itself. Meg Thompson writes, as part of a series called 'Drawing The War', that 'The Union was aware of Vizetelly’s whereabouts, and a bounty was offered to the Union Navy if they captured his sketches aboard any detained ships.' As a consequence of this situation, there were occasions on which Vizetelly's work, haivng been intercepted, would appear, uncredited, in Northern publications, such as Harper's Weekly.

Robert Ketchum, in his introduction to Bruce Catton's American Heritage Picture History of The Civil War, says 'the original sketches by the artists who worked for these illustrated weeklies had a freshness ... the engraver never caught when he redrew their work on wood blocks.' Well, whilst there's undoubtedly something in this, as some of Vizetelly's sketches reproduced here may perhaps illustrate, I also think that the engravings have certain qualities, mostly to do with a higher level of finish and detail (and also a certain nostalgic aura), that give them their own merit.

What is more certain is that the engravers didn't face the same arduous and dangerous day to day situations that a 'special artist' did. Just like journalists in all eras, there was the risk of being taken for a spy, and it's known that special artist [NAME?] died whilst a prisoner of Qunatrill's Raiders, perhaps under such a pretext. Vizetelly himself came under fire on numerous occasions, at Fredericksburg being only feet away from a soldier decapitated by an exploding shell, and on another occasion eliciting cheers from his Southern companions, as he raced back to safety from a spot that was growing too hot.

When Vizetelly took up with the ILN it lead to close to a quarter century of work, often in war zones, and not just in America, but also in Italy, Spain, and Egypt. Sadly Vizetelly's gung-ho approach did eventually lead to his death, when he and another British journalist, along with around 10,000 troops of the Hicks Pasha expedition, were wiped out in a massacre in the Sudan. Some sources say the best guess for where and when this occurred is that it was sometime in 1883, somewhere in the Sudan. But I did find one online document that was more precise, giving the place and time as 'near El Obeid, on November the 5th, 1883' [6].

All in all, I think Vizetelly's exploits in America during the Civil War make for a fascinating story, and his artwork and writings are an invaluable resource, both in their rawer annotated sketch states, and also in their more fully realised ILN format, as engravings, often accompanied by his lively reports from the scene of the actions depicted.

If you've enjoyed this article, please leave a comment. I would like to thank all the people involved in the online academic resources I used, in particularl the Harvard and Emory University archives. At the time of writing and posting, these were accessed here:

http://oasis.lib.harvard.edu/oasis/deliver/~hou00067

http://beck.library.emory.edu/iln/index.html

At the time of writing there is also a short piece on National Geographic's website:

http://ngm.nationalgeographic.com/2012/05/civil-war-sketches/katz-text

[1] Through the Cruikshank connection - George and his father Isaac - we can link this ACW-themed story to my normal sphere of interest, the Napoleonic era, as both Cruikshanks were formidable caricaturists, active in the golden age of satiricals prints, along with Gillray, Rownlandson et al.

[2] These two Vizetelly quotes appear in Cochran's April 61 NG 'Wintess To A War' article.

[3] This quotes comes from The Illustrated London News, vol. 38, no. 1096, pp. 601-602.

June 29, 1861, 'The Civil War In America'. Retrieved from http://beck.library.emory.edu/iln/browse.php?id=iln38.1096.165 (8/10/2014)

[4] Cochran, Ibid.

[5] Cochran, Ibid.

[6] From 'Historical Dictionary of War Journalism', by Mitchel P. Roth. Accessed via books.google.co.uk (8/10/2014)

No comments:

Post a Comment